The Bohr radius, denoted by the letter a, is the average radius of an electron’s orbit around the nucleus of a hydrogen atom in its lowest state (lowest-energy level). The radius is an approximately equivalent to 5.29177 x 10-11metre, which is a physical constant (m). 5.29177 x 10-9centimetres (cm) or 0.0529177 nanometers (nm). This span corresponds to around 1/10,000 of the wavelength of a blue visible light ray.

Bohr Radius

The Bohr radius is named after Danish physicist and philosopher Niels Bohr, who developed the so-called Bohr model of the atom (1884-1962). Atoms, according to Bohr, are made up of compact, dense nuclei with positive electric charge, which are surrounded by negatively charged electrons orbiting in circular patterns. Nowadays, scientists believe that the electrons surround the nucleus in spherical probability zones called shells, and that this is an oversimplification. The Bohr radius, on the other hand, is still a useful constant because it roughly indicates the smallest mean radius that a neutral atom may reach.

Definition and Value

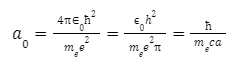

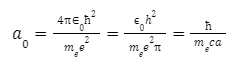

The Bohr radius is defined as

Where

- is the permittivity of free space,

is the reduced Planck constant,

me is the mass of electron,

e is the elementary charge,

c is the speed of light in vacuum and

o is the fine-structure constant.

The CODATA value of the Bohr radius (in SI units) is 5.29177210903(80)×10-11m.

Vacuum permittivity: The value of the absolute dielectric permittivity of classical vacuum is 0 (vacuum permittivity). It’s also known as the electric constant, the permittivity of open space, or the dispersed capacitance of the vacuum. It is a physical constant that is ideal (or at least close to it).

The Hydrogen Atom’s Bohr Theory

Rutherford’s Failed Planetary Atom

On the basis of Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden’s -particle scattering investigations, Ernest Rutherford suggested an atom model. Helium nuclei (-particles) were fired at thin gold metal foils in these studies. The majority of the particles did not scatter and passed through the thin metal foil intact. Some of the few who were spread were scattered backwards, meaning they recoiled. Backward scattering necessitates the presence of heavy particles in the foil. When a -particle collides with one of these heavy particles, it simply recoils, like a ball tossed against a brick wall. Because the majority of -particles do not scatter, the heavy particles (atom nuclei) must occupy a relatively small portion of the overall space of the atom. The vast majority of the space must be unoccupied or inhabited by particles of extraordinarily low mass. The electrons that surround the nucleus are these low-mass particles.

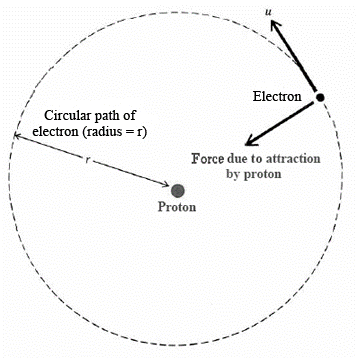

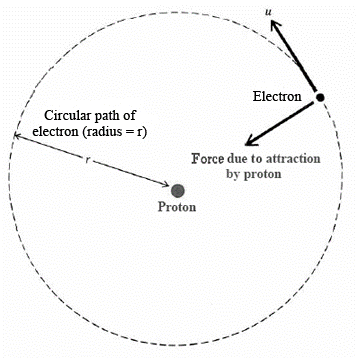

The Rutherford model has certain fundamental flaws. Because of the Coulomb interaction between oppositely charged particles, a positive nucleus and negative electrons should attract each other, causing the atom to collapse. The electron was thought to be orbiting the positive nucleus to prevent the nucleus from collapsing. The Coulomb force (described below) is used to shift the direction of velocity, similar to how a rope pulls a ball in a circular orbit around your head or how gravity holds the moon in orbit around the Earth.

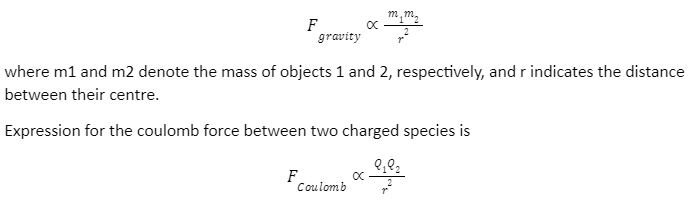

The resemblance of gravity and Coulombic interactions is the source of this idea, which shows that this approach is realistic. Newton’s Law of Gravity expresses the gravitational force between two masses as

with Q1 and Q2 indicating the charge of objects 1 and 2, respectively, and r indicating the distance between their centre.

However, there is a flaw in this analogy .An electron travelling in a circle is constantly accelerated because its velocity vector changes. When a charged particle is accelerated, radiation is created. This property determines how a radio transmitter functions. A power supply sends energy (electromagnetic radiation) to your radio receiver by driving electrons up and down a wire. The music encoded in the waveform of the emitted energy is then played for you by the radio.

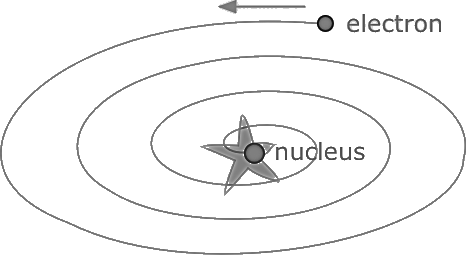

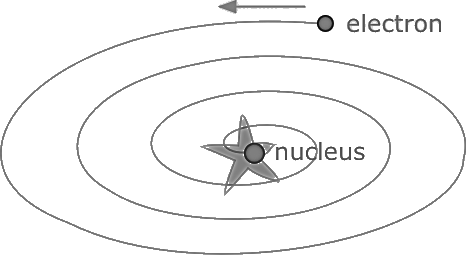

The classical death spiral of an electron around a nucleus.

The circling electron is losing energy if it is emitting radiation. The radius of an orbiting particle shrinks as it loses energy. The circling electron’s frequency rises to conserve angular momentum. As the electron approaches the nucleus, the frequency continues to rise. Because the frequency of the revolving electron and the frequency of the emitted radiation are the same, both fluctuate continuously, resulting in a continuous spectrum rather than the discrete lines visible. Furthermore, when the time it takes for this collapse to occur is calculated, it takes around 101l seconds. This suggests that nothing in the world could persist for more than around 10-11 seconds depending on atom structure.

Bohr Model

The line spectra studied in the previous sections reveal that hydrogen atoms absorb and emit light at specific wavelengths only. This discovery is related to the discrete character of a quantum mechanical system’s allowable energy. In contrast to classical mechanics, quantum mechanics claims that a system’s energy can only take on discrete values. This begs the question: how can we figure out what these permissible discrete energy values are? After all, Planck’s formula for the allowable energies appears to have appeared out of nowhere.

Despite the fact that Bohr’s reasoning is based on classical conceptions and so is not an accurate explanation, the reasoning is intriguing, thus we investigate this model for its historical relevance.

Conclusion

According to the Bohr Atomic Model, a small positively charged nucleus is surrounded by circulating negatively charged electrons in set orbits. He came to the conclusion that electrons with a distance from the nucleus had more energy than electrons with a distance from the nucleus.